Commentary on The 10 Principles of Maniphesto Part 2

Unity and Multiplicity

Our community enables true individuality. We respect the man and challenge the idea. We admire each other’s gifts. We approach disagreement with curiosity and mutual respect. We grow in discernment by engaging in vigorous discussion.

The question of diversity of thought in an organization is more important than we think. First of all, because we, as human beings, are very prone to cultic thinking—that is, blindly imitating people in a group because of the need to belong. Cults demand not only your time and money but the total submission of your personality (and your money). If a group, like Maniphesto, is going to avoid this, it has to have a self critical function, which does not crush the individual. The delicate issue is: how to keep the organization in a state of growth and vitality without destroying the diversity of voices in service of some imaginary ‘big other’.

Cults in their extreme ask people to ‘drink the kool-aid’, which may be a guru or just an ideology. And men’s groups are not immune to this. In ,Michel Butler’s brilliant lecture on the history of men’s groups, he has explained the multiple ways that men’s groups have gone astray, from incel cults to new age sensitives. If men’s groups are based on resentment or fear of women, for instance, they can become anti-women cults. If men’s groups are based on emotional catharsis, primitivism, and beating one’s chest and shouting in the woods, they can become rather ineffectual pagan cults. There are bodybuilding cults for men, militaristic cults, cringeworthy sensitive men cults—the potential for cultic behavior is endless.

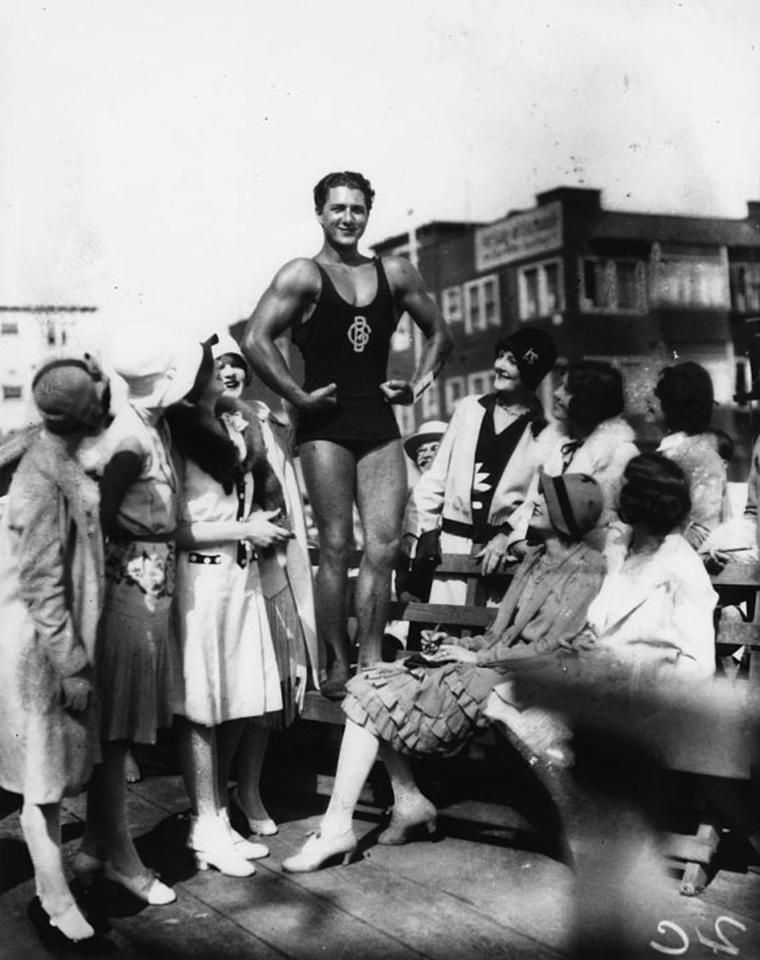

The problem with cultic thinking is often with image. We have a certain image of what a man is and we are told to adhere to that image. But what is a man? Do we have to define this? Certainly we should celebrate masculinity and the masculine man but what does that mean? Does a man have a big chest and a beard and a lot of muscles? Or can a man also be a scholar? Is a man someone who ‘acts’ or someone who ‘thinks’? And can a man be vulnerable and sensitive and still be strong? Of course, there are diverse types of men: some who love business, others who are introverts and visionaries, some who are warriors.

In the recent summer European Men’s gathering we divided men into warrior, priest, and merchant—but even within those roles there is an endless diversity. A good organization allows for all ‘personality types’ and even for some conflict between members. There must be a total respect for the person so that living dialogue can take place. The choice is, as Marshall Mcluhan once said, between dialogue and war. And a cult is always at war with the world, rather than in conversation with it.

The cult isolates itself from the world. It builds a wall around itself and its own ideological presumption. Conversely, the good organization has a membrane that is semi permeable: it opens and closes. It has some tolerance for eccentricity and difference, and it allows for some slack. It’s goal isn’t total efficiency but growth and innovation. This means that conflict is allowed, antagonism is allowed, a certain amount of disharmony and frustration are inevitable. But in a good organization people are allowed, and encouraged to be adults, and to fight and wrestle with the truth, because they feel that their peers respect and admire them and they are not being undermined or converted or cajoled or made into sheep. This is why a true unity requires genuine multiplicity.

Note: This is part 2/10 of a commentary on the 10 principles of Maniphesto

Responses