“The Angry Person is a Wilful Epileptic”: John Climacus on Anger

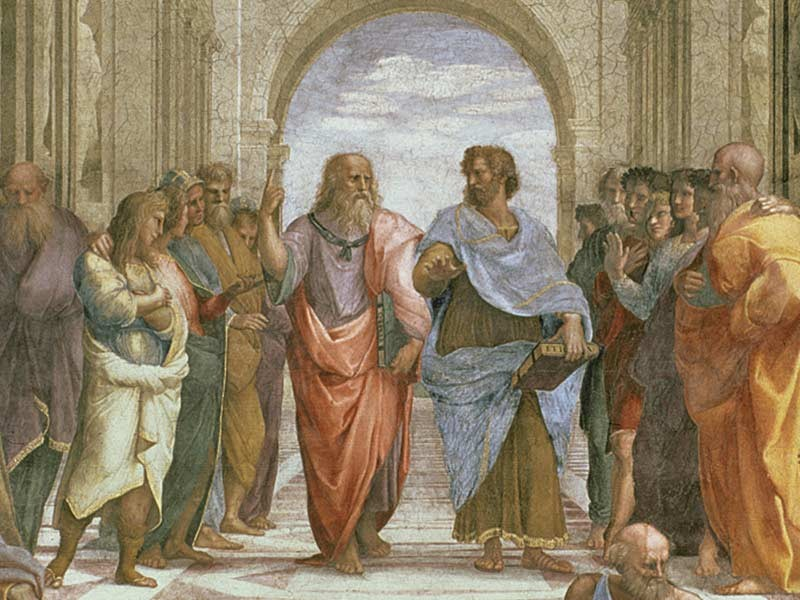

In this new blog series “Ancient Wisdom for the Modern World”, we will seek to learn from the intellectual and spiritual giants of the ancient world. It has aptly been said that the European philosophical tradition consists of a “series of footnotes to Plato” (A.N. Whitehead). While this oft-quoted statement is clearly an exaggeration, it cannot be denied that many of our most valued ideas and concepts have deep roots in ancient thought.

In Maniphesto, we recognize the important fact that we stand on the shoulders of giants. There is an infinite array of ways of being in the world, and on an individual level, we have been heavily influenced by our parents and our forebears in general. On a cultural level, we have also received a valuable heritage that can be described with words such as tradition or collective wisdom.

This indebtedness to the past goes all the way back to antiquity. Unfortunately, having an attitude of reverence towards our history and tradition is far from self-evident at the present time where historical figures, traditions and institutions are often criticised relentlessly for not living up to contemporary notions of morality, race, gender and sexuality. In Maniphesto, we resist such unforgiving “iconoclasm” (Editor’s note: how this phenomenon can be seen as a repeating of the iconoclastic movements of the past will be the subject of a future post) and insist on paying due homage to our past without being blind to its problematic aspects.

In this first entry, I will introduce the spiritual counsel given by John Climacus (6th-7th century AD). The monk John lived in a setting that hardly could have been more different than our own. Having dedicated himself to an austere life of asceticism, he found himself responsible for a community of brothers in a monastery on Mt. Sinai in Egypt. In order to assist fellow monks in their monastic formation, John wrote the book “The Ladder of Divine Ascent” which is still today recognised as a spiritual classic. In this work, John describes the spiritual life using the overarching image of a ladder comprising a number of steps which eventually lead to perfection. In what follows, I will focus on John’s advice related to the subject of anger (Step no. 8) since this is our current theme of the month in Maniphesto.

![]()

Analysing the negative aspects of anger, John states that “the first step in the cure should be a diagnosis of the cause of each disease.” In other words, our anger cannot be properly addressed if we do not know what is causing it. The reasons for anger are innumerable and therefore each person needs his own individual diagnosis. At the most general level, John says, the root causes of anger are to be understood as a “remembrance of wrongs” (i.e. inner resentment) or a “sign of presumption” (i.e. an inflated sense of self-importance).

John provides a number of practical suggestions on how to combat anger. An important element in the “treatment” is cultivating the ability to hold one’s tongue. The logic behind this piece of advice is the circumstance that “moments of anger” (i.e. angry outbursts) in John’s view can be exceedingly dangerous and might result in one’s “downfall”. He characterizes an angry person as a “wilful epileptic” who is not able to control his temper during his “seizures” and therefore risks saying or doing something self-destructive.

Contemporary society sees classical masculinity as toxic, and expressions as anger. In their efforts to live up to general expectations, we generally see a tendency for men to swing between unbridled outbursts of anger, to unhealthy suppression of emotion resulting in lack of energy. John believes that living in a community with other “hot-tempered men” can be very beneficial with respect to addressing anger. This somewhat paradoxical suggestion draws inspiration from the fact that “stones with sharp corners” with time become rounded by rubbing against other stones. To be sure, John’s vision of a monastic community is of a completely different character than the way our men’s groups operate in Maniphesto Core. But even so, living in a (physical or digital) community with other men is certainly a powerful remedy against a hot temper.

While John views anger in a predominantly negative light, he has himself observed that it can have a positive effect: “I have seen people flaring up madly and vomiting their long-stored malice, who by their very passion were delivered from passion, and who have obtained from their offender either penitence or an explanation of a long standing grievance.” In this way, resentment can sometimes be cured and broken relationships be restored through the expression of anger.

As our “Month of Anger” in Maniphesto Core draws to a close, let us heed the advice of the wise John Climacus!

Responses