Commentary on The 10 Principles of Maniphesto Part 5

5. Conciliarity

Working as a council of peers brings Hierarchy and Do-ocracy together. We are co-creative by design, providing the platform for men to engage and contribute actively.

What is the point of a natural hierarchy (as opposed to an arbitrary one), and why is any kind of hierarchy still necessary? Of course, if you try to do away with hierarchy, you will still find that, as George Orwell has pointed out, that ‘some animals are more equal to others’. Hierarchies—the ranking of higher and lower, better or worse, bigger or smaller, older or younger—will always pop up in any case, no matter how much you want to flatten them. (The mass social experiments in China and the Solviet Union attest to the terrible human cost of trying to eradicate inequality and flatten hierarchies.)

Creating hierarchies that are self aware and related to competence and achievement— rather than entitlement and class—will allow people to shine, and provide a vertical depth dimension to life, rather than a flatland of bland equality. We actually want a certain amount of inequality in our lives, no matter how unfashionable that sounds. If there were not some people who were greater than us, we would have nothing to aspire to; and if there were not some people who were lesser than us, then we would have no model for what not to do, nor would we have any capacity to lift others up.

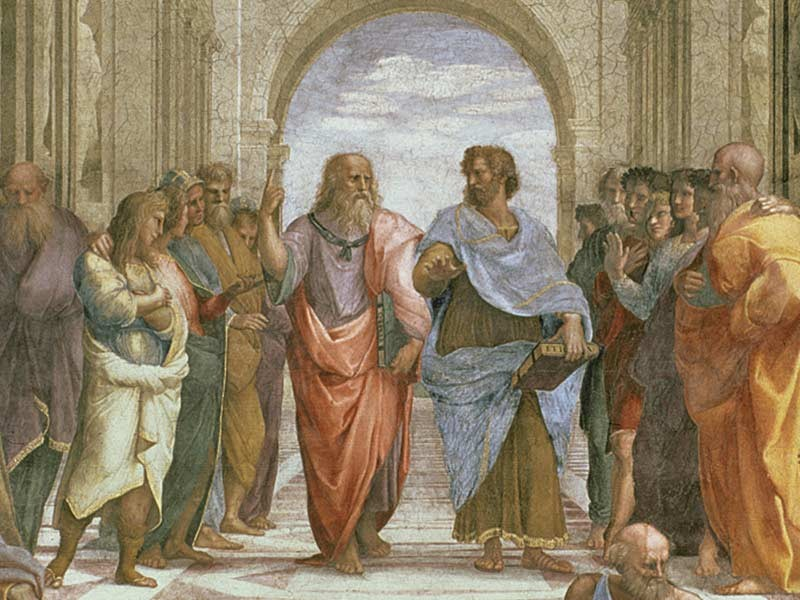

It’s obvious however that hierarchies have their pathologies and potential for tyranny. To prevent this, religious organizations have, in the past, placed God on the top of the hierarchy, so that no one person can play God or guru and so that human fallibility is recognized. A leadership council should be composed of a group of individuals who are competent, wise, and can make good decisions together. Conciliatory representation is how ancient and traditional institutions like churches operated to avoid the tyranny of charismatic or power hungry individuals.

In the context of Maniphesto, council members represent different backgrounds, skill sets, and qualities, and the leadership is diverse. Furthermore, leaders inspire men to inhabit leadership positions of their own, so that the council can eventually be taken over by younger generations. There should be a constant flow between the upper and lower; new blood needs to be injected into the council to keep it from becoming static and self-satisfied.

The council is not an elite power-grabbing group which seeks to hold on to its power; it is an organization based on wisdom and a certain altruistic motivation. This wisdom is transmitted to the younger generation in order to prepare them for leadership roles. What is important is that a transmission of skills and spirit take place between the council and the members of the community.

The council is not so big and democratic that it cannot make decisions; it is not so small and narrow so that its decisions do not represent the community. A position on a council is earned, not by entitlement but by competence—not through power drives, but through desire for service.

The council serves the community, which in turn serves the council—this creates a virtuous cycle where everybody benefits. This natural hierarchy is therefore respected because it provides tangible worth to the community, and to those who are leaders and learners. And the leader is the ultimate learner, which means humility and competence are the mark of council leaders.

Note: This is part 5/10 of a commentary on the 10 principles of Maniphesto

Responses